source: http://firstwefeast.com/eat/hood-chinese-food/

==================================

Q1: Are you a fan to try different foreign cuisine? Why or Why not?

Q2:

==================================

“It looks mad hood, but they got the best chicken wings I’ve ever had from a Chinese spot,” says Joell Ortiz, talking about a rugged-looking enterprise across from the Cooper Park housing projects in Brooklyn. Named Ho-May, the takeout joint’s muddy red-brick facade houses what the Slaughterhouse rapper describes as “two dirty little tables and a bulletproof-glass window.” Inside, a chef called Aku skips traditional Chinese fare in favor of menu staples like chicken-wing combos with pork-fried rice, beef and broccoli sluicing around in an MSG-spiked gravy, and even french fries. Sugary barbecue sauce and sachets of ketchup are the condiments of choice.

Ho May is what a certain swath of New Yorkers—particularly those, like Ortiz, who grew up with hip-hop informing their lingua franca—would categorize as “hood Chinese.” It’s not a restaurant type, like izakaya or gastropub,that you’d find while narrowing down your search results on Yelp. But people in the know can spot it when they see it: a neighborhood hole-in-the-wall serving primarily carryout meals in styrofoam containers, selected from a garishly lit photographic menu and served from behind bulletproof glass. Seating is typically minimal, if not nonexistent, and the options veer more towards fast food than anything you’d find at even the most Americanized sit-down Chinese restaurants.

“These Chinese places are usually found in [poor] neighborhoods and they’re cheap. The food is actually similar to that of Spanish and black culture, with a lot of fried products,” explains Ortiz. “No one goes into a Chinese hood spot and orders authentic Chinese food; it’s not like we go and ask for the kung-pao-Szechuan-noodle delight. We go in there and get chicken wings, french fries…things that are close to what we eat anyway.”

“The taste of these dishes leans more towards the fast-food or soul-food palette,” says food scholar Adrian Miller. (Photo: Yelp/SS)

Like the remixed tacos of Compton, this genre of Chinese food is rooted not only in economics (providing cheap meals to low-income, traditionally non-white neighborhoods), but also the forces of culinary assimilation—in this case, Chinese businesses catering to a largely underserved black and Latino population that surrounds them. As food historian Adrian Miller explains, this cross-pollination dates all the way back to the 1890s. “You had Chinese restaurants in New York City welcoming black customers,” he says. “They were one of the few places where African Americans could go out and eat that wasn’t an African American establishment.” As such, African Americans were among the first adopters of pseudo-Chinese dishes like pork-fried rice and chop suey that eventually went mainstream.

As cultural and food traditions fused together, the makeup of the urban fast-food Chinese menu took shape. “Fried chicken, fried rice, french fries, and beef with broccoli are the defining things on the menu,” says Jennifer 8 Lee, the author of The Fortune Cookie Chronicles.

“EARLY CHINESE ENTREPRENEURS WANTED TO SHOW OFF THE BEST OF THEIR CULTURE, BUT OFTEN THEIR AFRICAN-AMERICAN CUSTOMERS WERE ASKING FOR THINGS THAT WERE MORE SIMILAR TO SOUL FOOD,” SAYS FOOD SCHOLAR ADRIAN MILLER.

Much of this influence is indebted to soul food, whose flavor profiles were incorporated early on. “Early Chinese entrepreneurs wanted to show off the best of their culture, but often their African-American customers were asking for things that were more similar to soul food,” says Miller. “The taste of the dishes leans more towards the fast-food or soul-food palette, so it’s got to be stuff that’s got more fat in it, and it’s got to be sweeter.”

(The origin of french fries on the hood Chinese menu remains a mystery, although Lee mentions a mainstay Chinese dish in Ireland called a three-in-one that consists of fried rice, gravy, and french fries.)

In a blog post named “In the Hood like Chinese Wings,” pop-culture rabble-rouser Eddie Huang brings the hood-Chinese conversation up to date, explaining how the phenomenon is not without its complicated race politics.

“We fucking love walls. Whether it was the Great Wall, bullet proof glass in take out joints, or cubicles that arrest most of our people these days, our approach is to say ‘I won’t bother you and you don’t bother me.'”

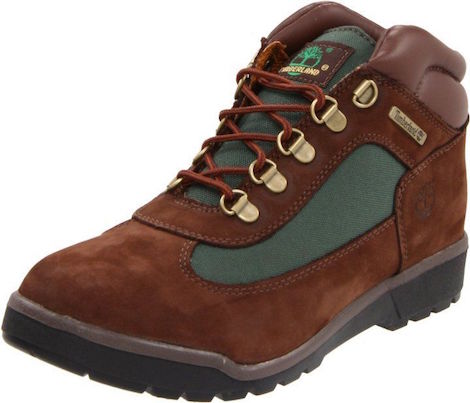

Like Huang, many New Yorkers have reference points for these places—especially the rap world, which has solidified hood Chinese relevancy in mainstream media. “This is Carhartt jackets, Timberland boots unlaced, this is Champion hoodies, chicken wings and french fries,” raps Joell Ortiz on the introduction to the track “Hip-Hop.”

“LIKE THE REMIXED TACOS OF COMPTON, THIS GENRE OF CHINESE FOOD IS ROOTED NOT ONLY IN ECONOMICS (PROVIDING CHEAP MEALS TO LOW-INCOME, TRADITIONALLY NON-WHITE NEIGHBORHOODS), BUT ALSO THE FORCES OF CULINARY ASSIMILATION.”

The cult flick Paid In Full opens with the rapper Cam’ron and his cronies holed up in Harlem back in ’86, plotting power moves while chowing down carryout staples like spare ribs and fried rice, quaffing champagne, and complaining, “They ain’t put no fuckin’ soy sauce in the bag, man.” (Cue Cam’s classic declaration, “Fuck the soo-ey sauce!”) Staples from the hood Chinese menu have also been flipped into hip-hop slang: Nicki Minaj and A$AP Ferg are the latest generation of New York emcees to have referenced “beef and broccoli”–colored Timberland boots (Big Daddy Kane famously rapped, “Come in the hood flippin’ the chicken-and-broccoli Timbs”). And on his hit “Learn Chinese,” the Chinese-American rapper Jin declared, “This one goes out to those who ordered four chicken wings, pork fried rice, and rolled dice in the hood.”

Modern food trends have ushered in a more adventurous palette for a new generation of New Yorkers: Cody B Ware from the Queens-based crew World’s Fair says his idea of a Chinese food fix is to head to Flushing to score a dozen chili oil dumplings for five bucks from White Bear, “a place that’s like the size of a closet.” But just as hip-hop has cemented itself as the soundtrack to the city, the hood Chinese spot has survived as the chief provider of its denizens’ oily fuel.

The so-called “Beef & Broccoli” Timberland boots got their nickname from a popular carryout Chinese dish.

Back in the ’90s, DJ Premier’s production touch was behind brawny New York City rap classics for Biggie, Jay Z, and his own group Gang Starr. While holed up in the legendary D&D Studios, sessions became filled with the aroma of the nearby Chinese place Number One Kitchen. “When me and KRS-One were making Return Of The Boom Bap, we’d always order there,” he recalls. “KRS would get the shrimp with lobster sauce.”

Premo’s fellow boardsman Statik Selektah says that Ortiz put him on to the greasy delights of Ho May: “They definitely have the best Chinese wings around, although last time I got sick from eating one too many.”

These days Ortiz has moved away from Ho May’s delivery zone to more salubrious climes, but he remains a champion of its no-frills menu. “I have a new neighborhood Chinese spot around my way, but it’s nowhere near as good as Ho May,” he admits. “It’s more clean—maybe that’s why I don’t like it.”

留言列表

留言列表